Introduction

The ship used in the mission is a critical factor in determining the mission's success or failure.

The ship must be fast, to ensure efficient and proper use of resources, as well as allowing rescue and supply missions to and from Mars as quickly as possible.

It must be resilient to failures and accidents, which will surely happen over the first, as well as consequent, missions to and from Mars.

It must have sustainable and reliable power generation, allowing for critical medical equipment, usage of the centrifuge, and backup thrusters.

And finally, it must support the crew, especially in their health, to ensure they are fit and prepared once on Mars.

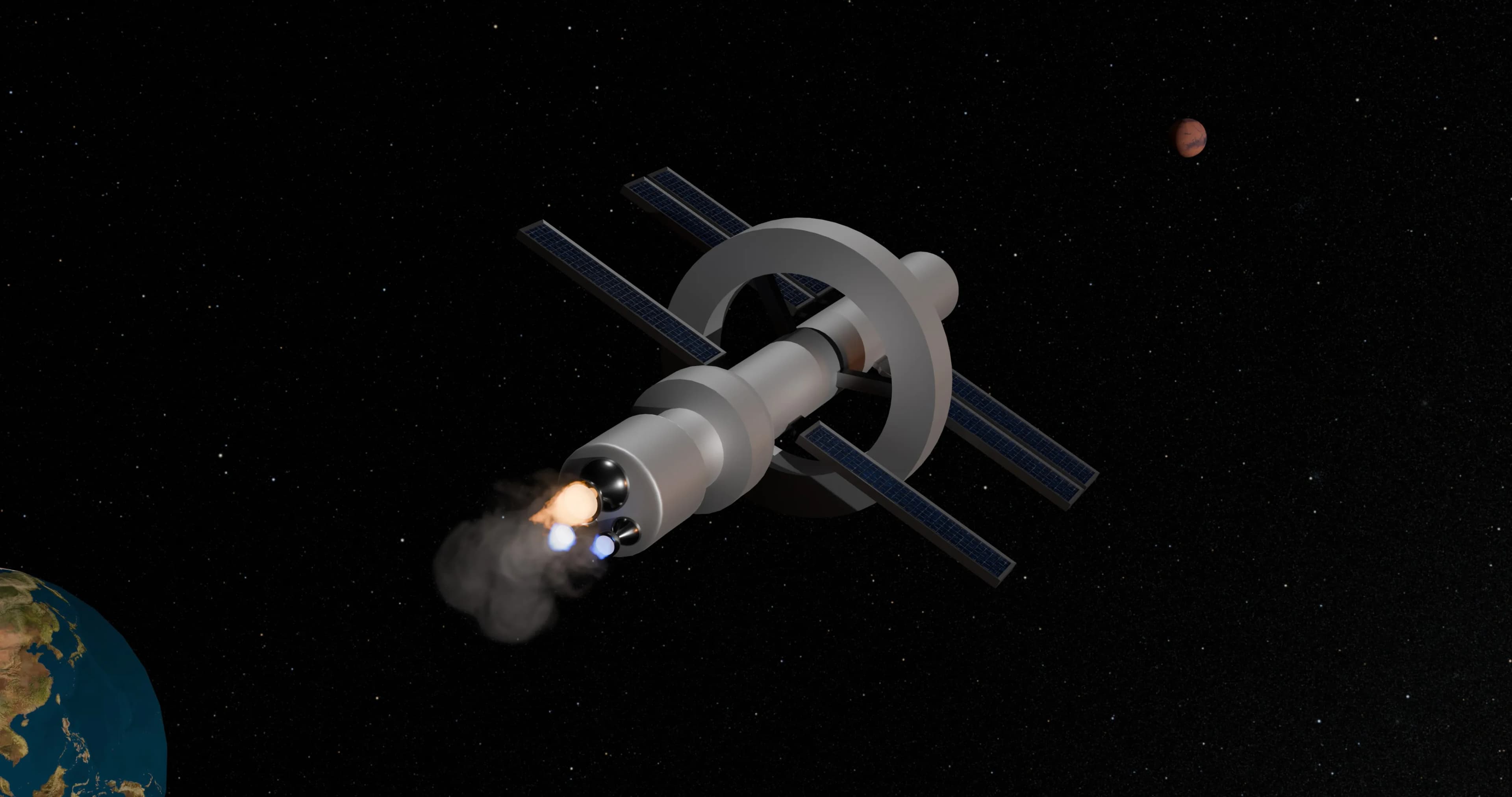

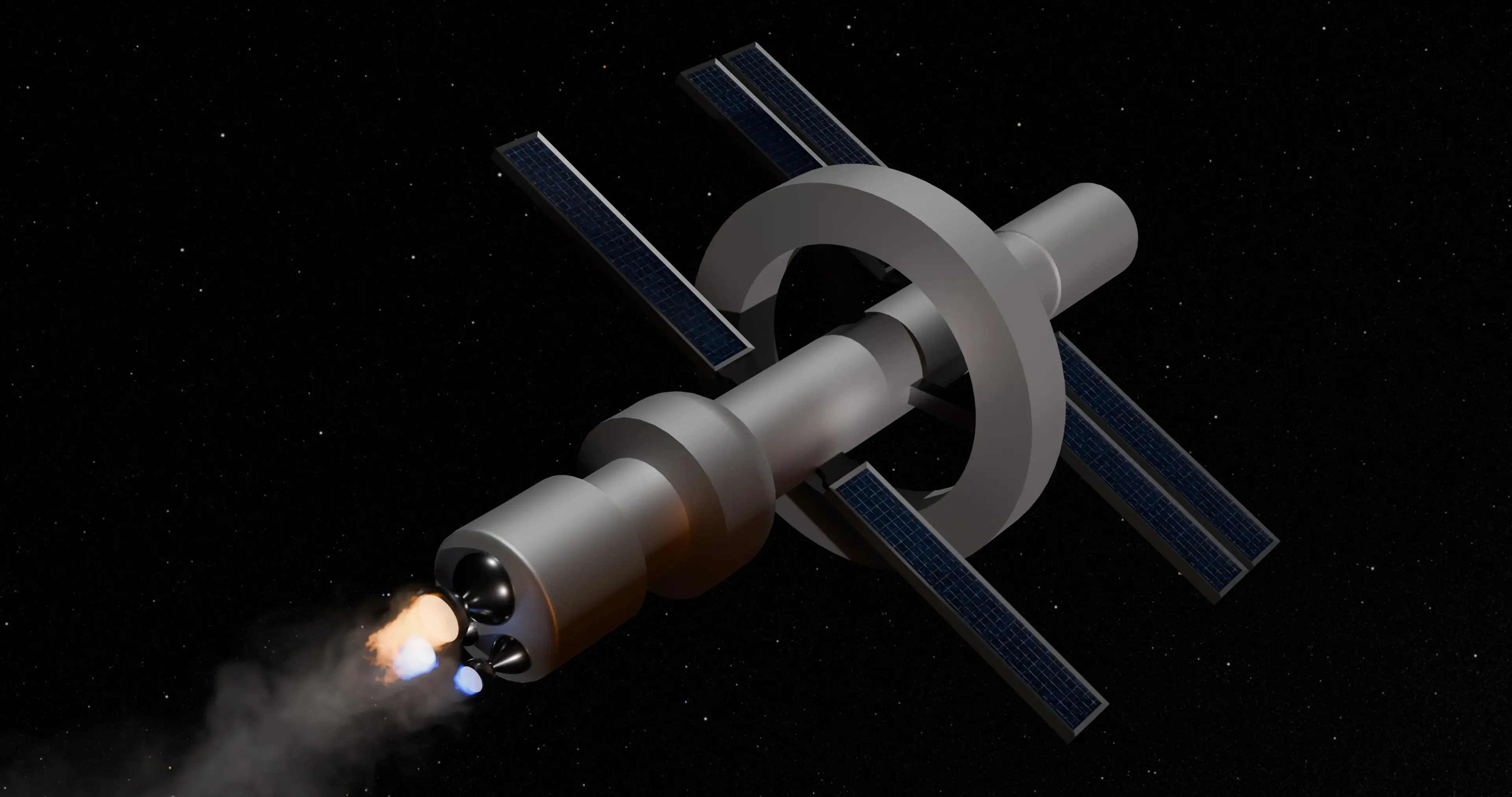

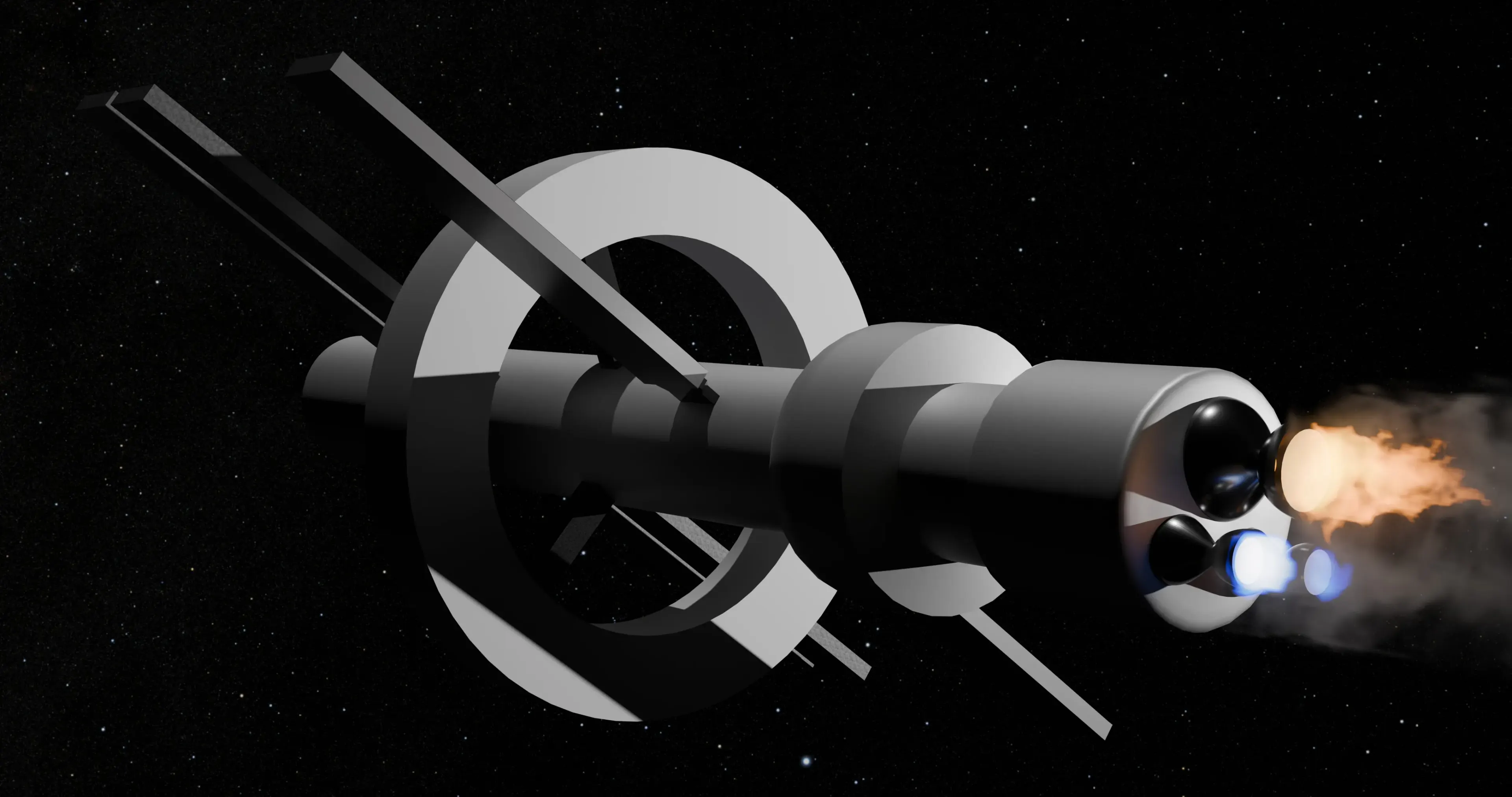

The final ship design, the RUBBER I, is shown below in Figure 1 and Figure 2, included with an artistic representation of Earth, Mars & Sun.

Ship Design

General Design

The General Design of the RUBBER I is in a way where it is able to be used for many subsequent missions to and from Mars. Everything in the spaceship is based around the idea of reliability, reusability, modularity and to be resilient to failures and accidents.

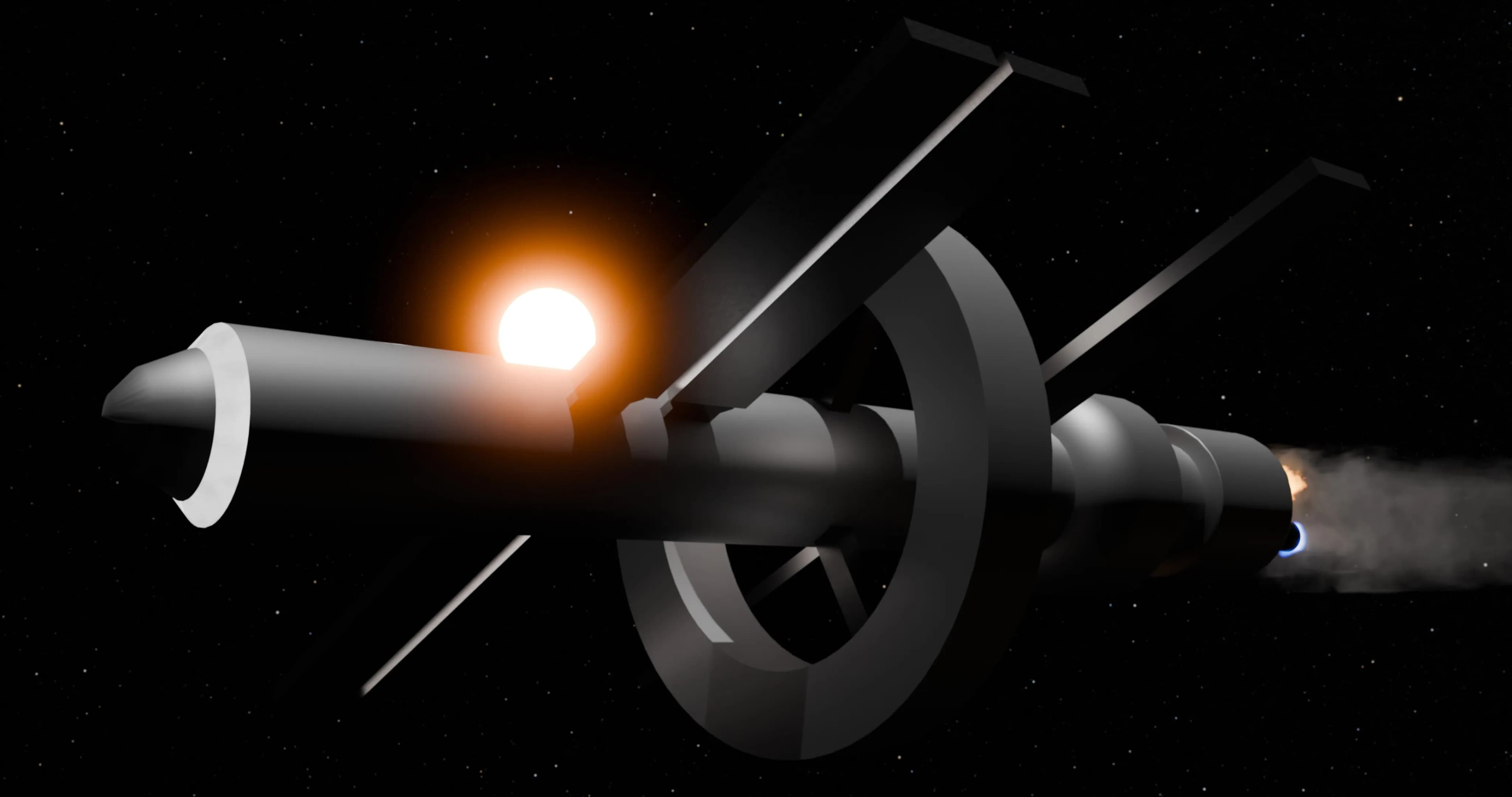

The design is also highly inspired by The Hermes in the movie The Martian. (Figure 3) Although this may seem to detract from the design, this actually allows for a template for the fine details of the design (which have not been included in the model due to time constraints), and the design did take reality into account. (Koberlein 2015)

Segmentation

Modularity

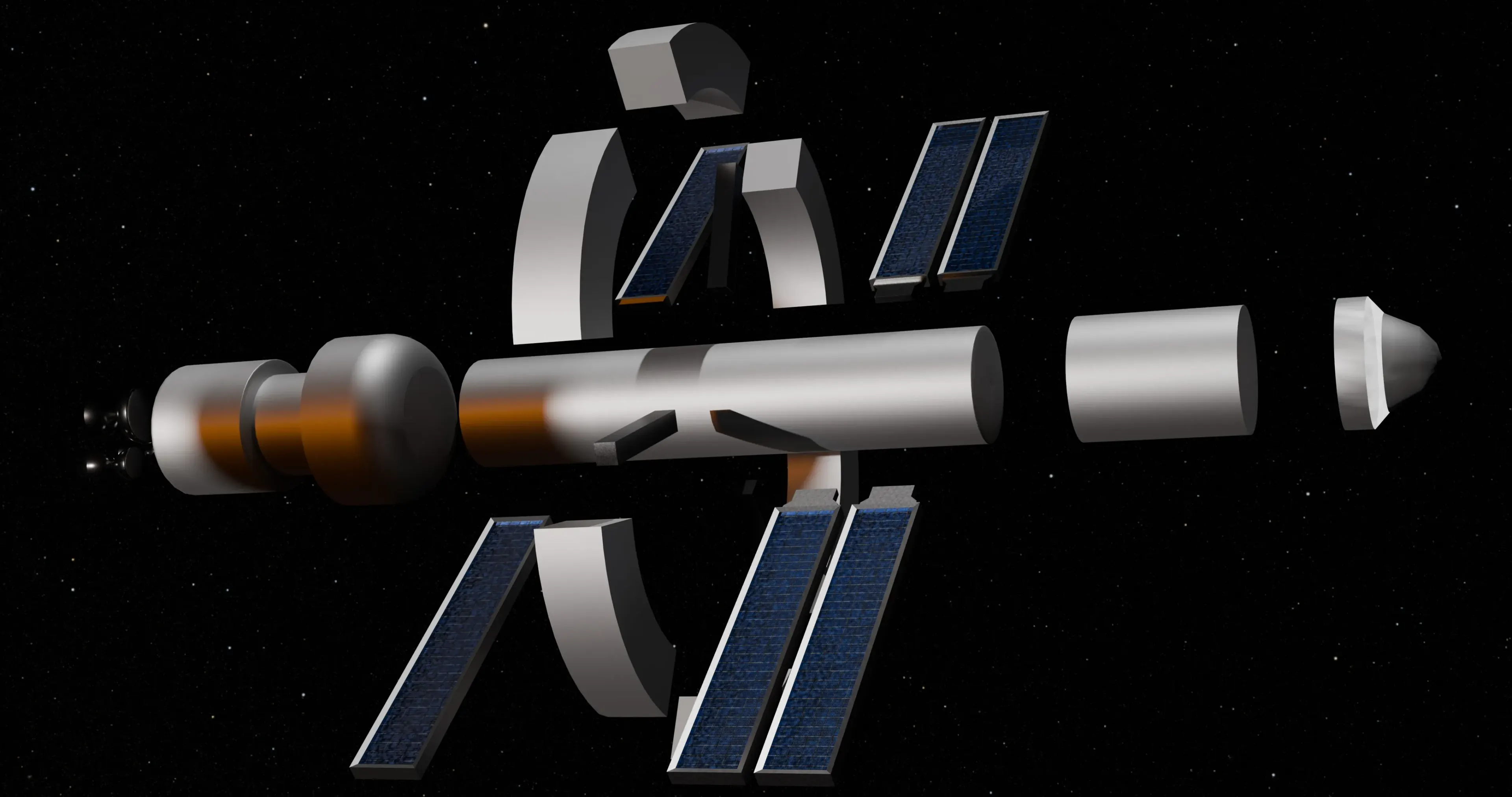

The RUBBER I is split up into 22 Modules. These modules are, and are shown in Figure 4:

- 1x Nose & Cockpit (5.57m by 5.57m by 5.01m)

- Where the ship is controlled

- 1x Front Module (5.57m by 5.57m by 7.25m)

- Dedicated docking module; Connects nose to middle module

- 1x Middle Module (5.32m by 5.32m by 21.5m)

- Main power provider; connected to solar panels; connected to centrifuge; main astronaut living area

- 1x Back Module (8m by 8m by 14.8m)

- Stores the fuel tanks; connected to the exhaust locations

- 1x Chemical Exhaust (3.26m by 3.26m by 3.1m)

- Main powerful engine, used to get out of orbit (Discover More ->)

- 2x Nuclear Exhaust (1.86m by 1.86m by 2.63m)

- Main engines used during the trip from Earth to Mars (Discover More ->)

- 6x Solar Panels (16.9m by 3m by 0.66m)

- Main source of power for the ship (Discover More ->)

- 3x Centrifuge Travel Poles (2m by 2m by 6.5m)

- Connects the main module to the centrifuge

- 6x Centrifuge Modules (6.51m by 8.65m by 3m)

- Split up sections of the centrifuge; provides artificial gravity for the crew (Discover More ->)

This split-up of the ship, especially separating key areas such as the thruster, fuel tanks, main crew area, centrifuge, solar panels, and the cockpit, allows for parts to be replaced and repaired easily in the future, ensuring that the RUBBER I can continue having the state-of-the-art safety, cryogenic, power and engine systems.

Furthermore, this separation of modules allow for easy expansion of the RUBBER I in the future.

Discover why we split the modules up the way we did in Module Reasoning! (Part of the Building Section)

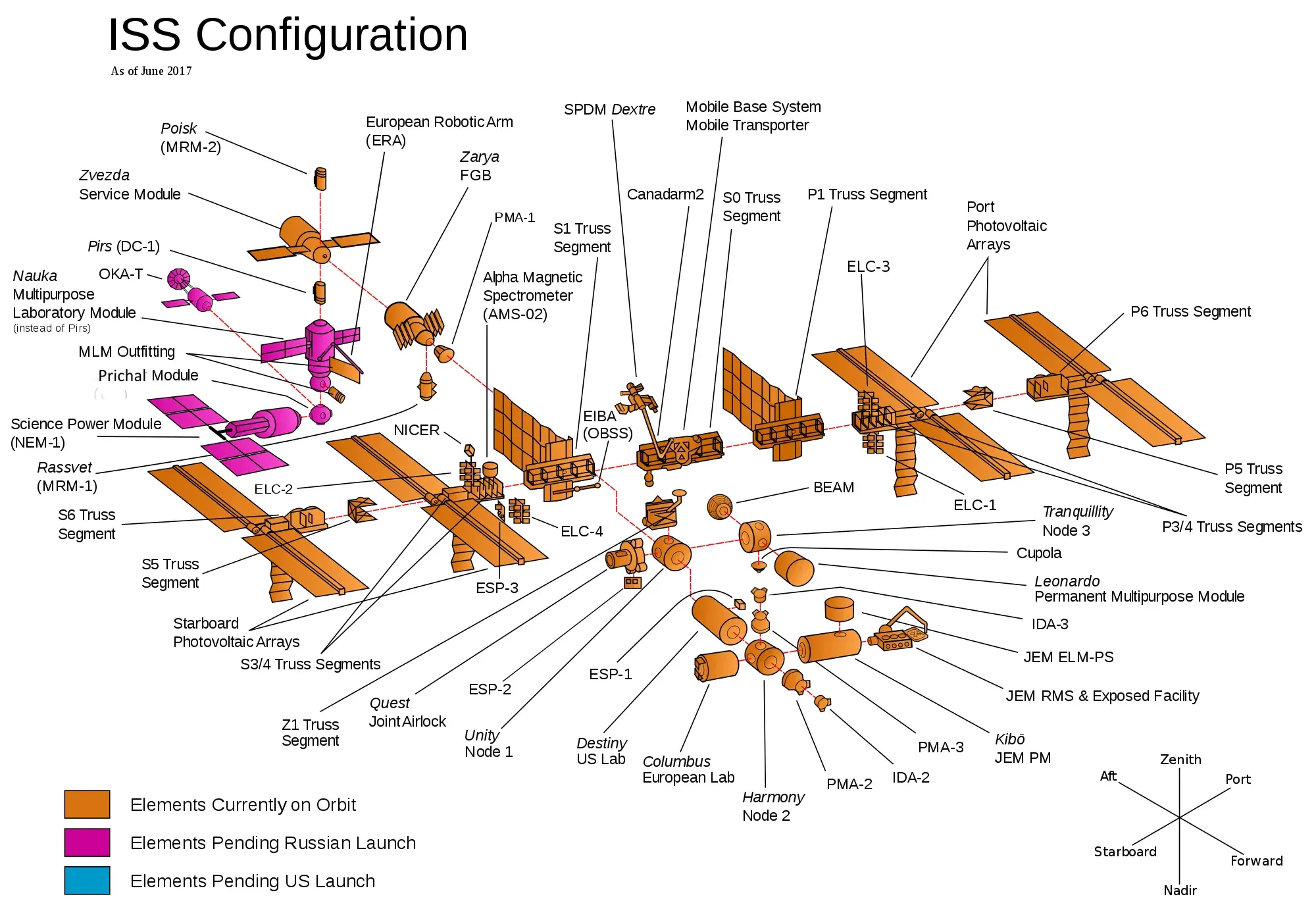

This idea of modules for the RUBBER I was initially from the modules of the International Space Station (ISS). The modules of the ISS are shown in Figure 5.

Redundancy

With the modules allowing for segmentation of the spacecraft, in the event of a failure or breakage of a given module, the module can be removed, and the spacecraft will still survive. This is conducted through redundancy.

For example, in worse-case scenario, where the fuel tank and main thrusters module must be disconnected, the electronic thrusters in each module allow for the RUBBER I to make it back to Earth safely.

Furthermore, this is accomplished by storing equipment and critical resources in multiple places, allowing the crew to survive, and perhaps continue the mission, in the event of sudden losses of modules.

Centrifuge

The Centrifuge is a large part of the spaceship, being a vital support for the crew, and the presence of it ensures the RUBBER I's relevancy, reliability and usability for many years and missions to come. This is because the Centrifuge generates artificial gravity, in the Zero G environments of space, allowing crew members to perform exercise activities and other daily tasks in a 'normal' environment, preserving their physical health and fitness, ensuring they are at their maximum capabilities once on Mars.

The centrifuge will be mostly used as an exercise and wellbeing facility.

Is this Really Needed?

Yes! Living in zero G or low amounts of gravity can lead to:

- Bone Loss & Structural Issues (Marks 2017)

- Cardiovascular Issues (Marks 2017)

- Immune System Issues (Marks 2017)

- Bone and Muscle Fatigue

This will lead to significant decreases in productivity, as well as potential diseases and death in the crew.

Why so Large?

The RUBBER I is a very big spaceship, coming in at a full size of 35.2m (W) by 20m (H) by 53.7m (L). Of course, because of the modularity factor in the design, the spaceship can easily be expanded lengthwise, and even widthwise or heightwise, if needed.

This large size is the critical factor which allows for the resilience of the mission, through the previously mentioned factor of Redundancy. Without the large size of the RUBBER I, effective usage of segmentation, modularity and redundancy would not be possible.

Furthermore, the large size allows for the transport, confort and facilities to support many people, including the 50 Astronauts planned for the initial mission.

Power

What Requires Power?

There are five main sections of the RUBBER I which requires electricity:

- The Centrifuge

- Backup Electronic Thrusters

- Cryogenic Cooling for Liquid Hydrogen (Needed for Nuclear Engines)

- Life Support, including Water Recycling

- General Electronic Equipment

Solar Panels

One of the main power sources, of which will be on the RUBBER I, is Solar Panels, as shown in Figure 6.

There are 6 Solar Panels, each of which has a photovoltaic cell surface area of 37.5m 2 , of which will be equipped with NERL's latest best solar cells, which performs in space with an efficiency of 35.5% the power of the Sun per area, when equipped with mirrors and lenses on top of the cells, in order to concentrate the photovoltaic energy to the equivalent of 92 suns. (Physics World 2021)

In Earth Orbit, where the Sun's solar energy is around 1370 Watts per m 2 , (Bereau of Meteorology 2024) this works out to around 51,375 Watts per panel. Taking into account the efficiency factor, one solar panel produces around 18,238.125 Watts per panel, or around 109,428.75 Watts for all 6 Panels. Due to factors such as incorrect positioning, or malfunctions, this may be only around 80k Watts.

On Mars, where solar power is around 43% less (Gilbert 2022), the panels produce around 47,054.3625 Watts under optimal conditions, and factoring for the inevitability of inefficiency, this may be around 30k Watts.

This amount of power is much more than needed for the usages of the electric thrusters (which can use as little as 70 watts) and the centrifuge. However, this large power production allows for the inevitable variance of solar power, miscalculations, failure of panels, and expansion of services on the ship which require electricity.

Nuclear Power

In addition to solar power, there is the potential for usage of nuclear power to power the RUBBER I, making use of NASA's MMRTGs. These produce power through the slow decay of radioactive materials, making it a viable backup power option in the event of a mass electronic failure and/or loss of the main connection modules.

Although these do not produce much power, only around 110 Watts in some designs, they can still be used as an effective backup power source, considering the low power consumption of some models of electronic thrusters.

Usually, Plutonium-238 is used, which produces mainly alpha particles in its decay. This is not very dangerous to humans, as these particles can be blocked by a simple piece of paper, or just your skin. However, some precautions and shielding would need to be taken, due to risks such as the release of beta and/or gamma particles, as well as the risk of powderization and subsequent inhalation by the crew. This will require some nuclear shielding, but it will not be extremely heavy or costly.

Batteries

In addition to power generation, the RUBBER I will include storage for electricity in each module, in the event of electrical failure and/or module separation.

Engines

Chemical Engines

As with most major spaceships, the RUBBER I will have a chemical engine, as shown in Figure 7. This will run off normal rocket fuel, but will only be used in the event where a large thrust is needed, such as an initial boost to exit orbit, and/or large corrections where time is not of a concern.

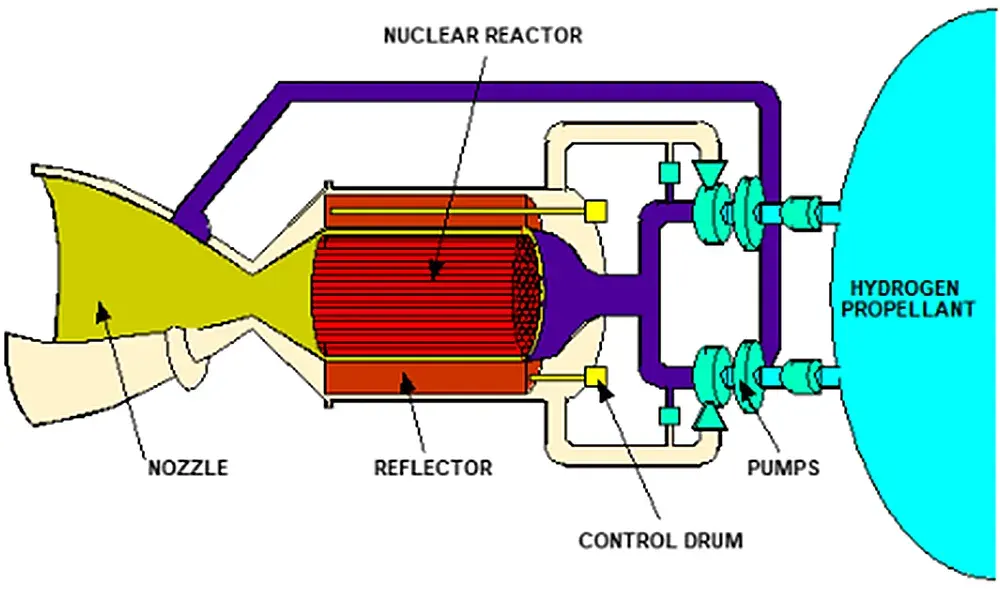

Nuclear Engines

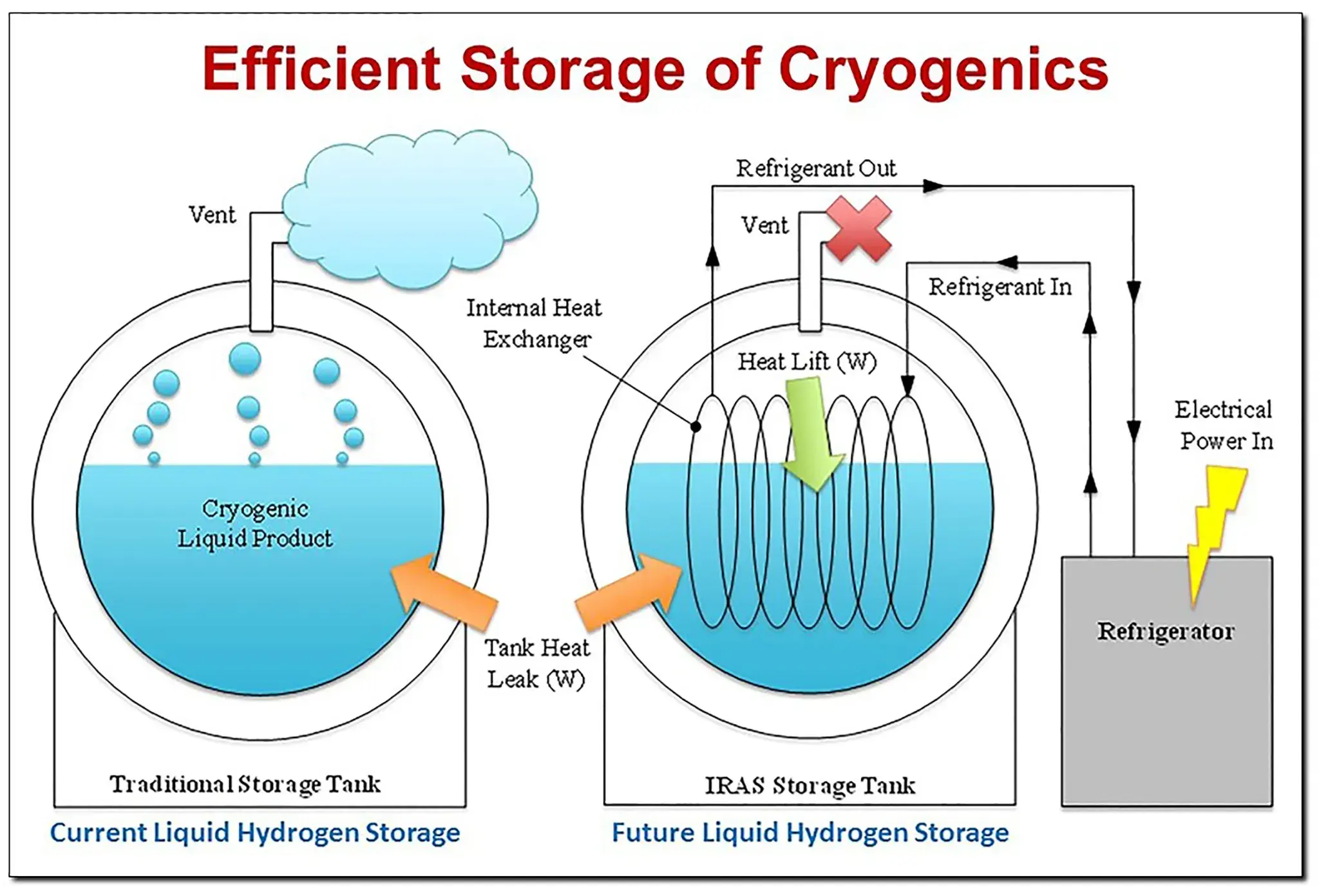

Unique to the RUBBER I, there will be Nuclear-Powered Engines. These engines consume Liquid Hydrogen. The RUBBER I will be using a method from NASA, which instead of re-cooling the hydrogen each time, will keep it as a liquid, increasing the amount we can store in a given space, and decreases power costs. This method is shown in Figure 8, and the inner-workings of the Nuclear Engine are shown in Figure 9.

The benefits of using Nuclear Engines is that it is possible for the RUBBER I to reach Mars in only ~45 days, rather than 7 months. (Young 2021) This is achieved as Nuclear Engines have much better fuel efficiency, meaning they can allow the RUBBER I to accelerate to great speeds, despite their lower thrust.

Electronic Engines

Electronic engines serve as the backup engines for the RUBBER I, and are on each module. These engines also allow for small adjustments in course, as well as providing sustainable continuous thrust during orbits of Mars and Earth, when coupled with the Solar Panels. These Electronic Engines consume very little power, and can provide very short bursts of high thrust.

Equipment

The RUBBER I will include lots of equipment, including, but not limited to:

- Life Support Equipment

- Spacesuits

- Liquid Oxygen, Hydrogen and Fuel Tanks

- Batteries

- Thruster Controls

This will allow the crew with the supplies and support it needs to thrive, both on the RUBBER I, and once on Mars.

Building

How to Build & Launch?

Because of the sheer size of our rocket, it is not feasible to launch it from Earth. Therefore, we will have to build it in space.

This will be done in Low-Earth Orbit, to reduce the strain, resource cost and monetary cost of the launches required to do this.

This is another reason why the RUBBER I is split into modules; to allow for the easy transportation and assembly of the spaceship.

SpaceX Starship

The building process, as well as transport to and from the RUBBER I to Earth, will use the SpaceX Starship, which recently completed its 4th flight test, of which was a success. (ABC News 2024)

This is because of two main reasons:

Capacity

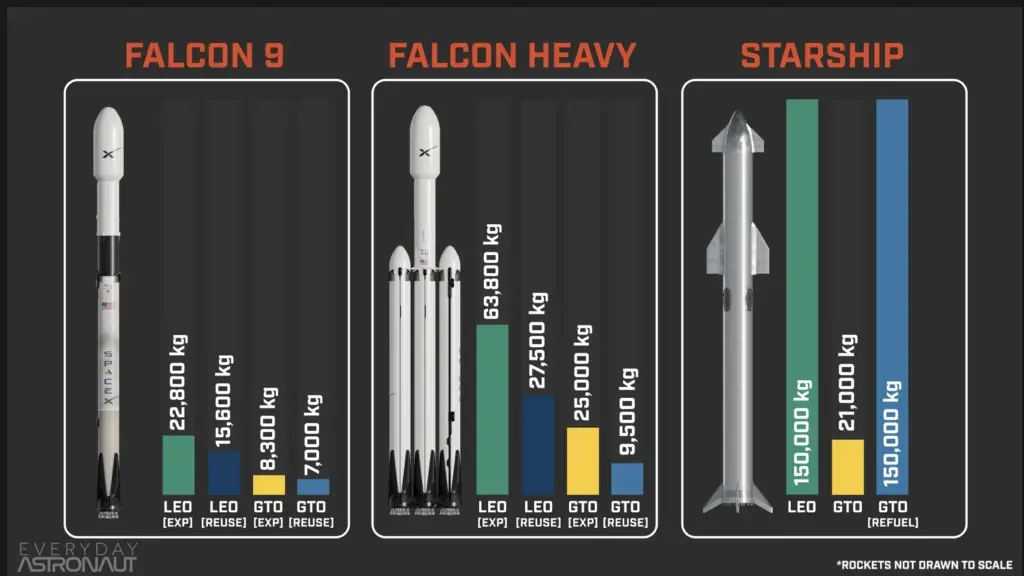

The Starship is the current spaceship with the largest capacity, in terms of weight, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 9 shows the maximum payload weight to different points of orbit, with LEO being Low-Earth Orbit, and GTO being Geostationary Earth Orbit, where the speed required to keep the rocket in orbit means that the rocket is always above a certain part of the Earth.

The Starship is also the spacecraft with the highest volume, with a maximum payload volume of a cylinder that is 8m wide and 22m tall. This maximum volume was a major factor in the separation of the modules of the RUBBER I.

Cost

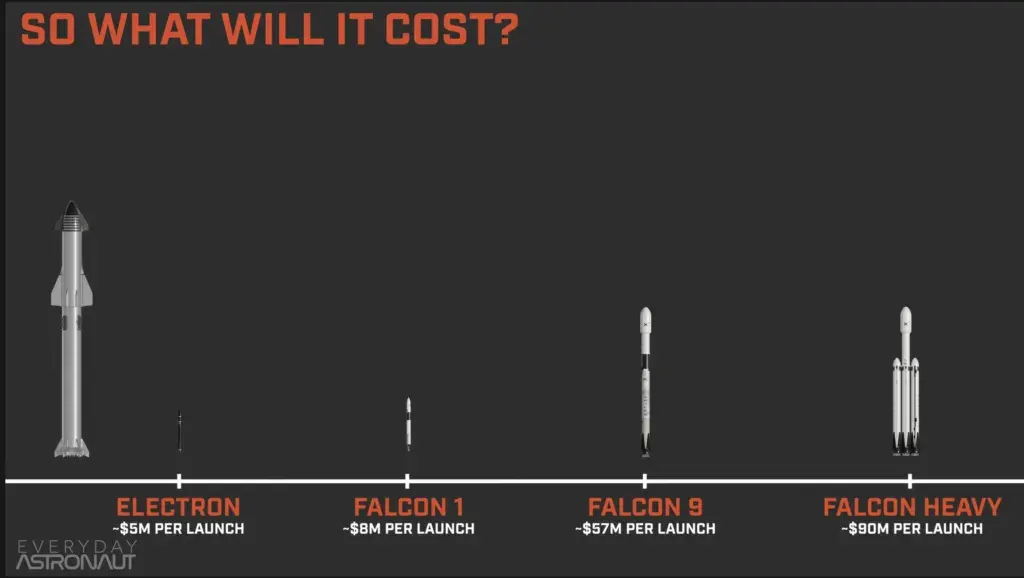

The Starship is also incredibly cheap to launch, due to its design meant to be completely reusable. The cost of a launch of a Starship is compared to other rockets in Figure 11.

Low Earth Orbit

The construction of the RUBBER I will take place in Low Earth Orbit, rather than Geostationary Earth Orbit. This is because of two main factors:

- Reduced cost of fuel

- Remove need of Starship mid-trip refuels

Furthermore, as future orbits the RUBBER I will take will also be low, the initial exit from Low-Earth Orbit must be conducted in the future anyways.

Module Reasoning

Main Modules

The main modules (nose, front, middle & back) were split up based on their functions, and to ensure that they do not become bigger than the maximum volume of the Starship (8m diameter by 22m length cylinder).

Solar Panels

The solar panels can be easily bundled together, due to their small width. In fact, they could even be bundled with other components, such as the nosecone and the travel poles for the centrifuge.

Although photovoltaic cells are quite heavy, according to Ecoflow 2022, commercial solar panels weigh around 5-10kg per m 2 . Therefore, this would be around 375kg per panel, and factoring in the use of non-commercial solar cells and the extra reinforcements that may be needed, this could increase to around 750kg per panel. However, this is still feasible, but will require more launches.

Centrifuge

The centrifuge is of an interesting shape to transport. Because the edges of the centrifuge are straight, and the edges of the payload cylinder are… round, the size is further limited.

For all future calculations, the centrifuge is viewed side on, with the origin of the circle being the point in the centre of the centrifuge.

The maximum size for a centrifuge module, due to the straight sides, is 7.42m by 3m by 22m.

This was calculated via:

y^2 = 16 - 1.5^2

y^2 = 16 - 2.25

y^2 = 13.75

y = 3.71

Max Height = y * 2

Max Height = 7.42

Essentially, we find the height (y) of a circle, where the sides are 1.5m offset from the origin.

(Because the centrifuge module is 3m wide, 1.5m each side)

Because the 3m width of the centrifuge is fixed, the optimal position is where one dimension of a module is greater than 7.42m, and the other is equal to 7.42m.

The first dimension to surpass 7.42m is the y value, or the height, of the module. This happens once 'x' value of the circle surpasses 3.30m, which is a tiny width.

This was calculated via:

x^2 = 100 - 7.42^2

x^2 = 100 - 55.0564

x = 6.70

Width: 3.3m

The width reaches 7.42m once the height is around 9.66m.

This was calculated via:

y^2 = 100 - (10 - 7.42)^2

y^2 = 100 - 2.58^2

y^2 = 100 - 6.0564

y^2 = 93.3436

y = 9.66

Height: 9.66m

However, this is not going to be an equal separation of the modules! To find the optimal separation for an equal module setup, which improves structure and keeps the average space per module equal, we found the optimal angle between the start and end of the module. The found angle was 68.37°.

This was calculated via:

a = cos^-1((10-7.42) / 7)

a = 68.37°

Angle - 68.37°

Although / 7 may look weird, this is because cosine uses the ratio of adjacent vs hypotenuse.

We rounded this down to the nearest angle, which had equal parts in 360°. This resulted in 6x60° Modules.

Although this may seem small, in reality, each module has around 10.47m by 3m of floor.

Getting On and Off

Stay in Orbit or Land?

The RUBBER I will not land on either Earth or Mars, but will instead stay in the Low-Earth/Low-Mars Orbit of each. This has two main benefits:

- Preventing the deterioration of large acceleration periods and from the continuing exit and entry of atmospheres

- Preventing the need of the large logistics and resources of launching such a large spaceship

We also chose Low Earth/Mars Orbit, instead of Geostationary, as it would reduce the strain and the necessary capabilities of the transport vehicles, reducing their needed weight and size, as well as the monetary and resource cost per launch.

However, as we are not landing, we need a way to get from Earth and/or Mars to the RUBBER I.

Earth

Transport to and from Earth will be through SpaceX Starships. Details about this, and why we chose to use the Starship, is in SpaceX Starship.

Mars

Transport to and from Mars will be through SpaceX's HLS modules. Concepts, and designs have been made for a similar HLS for NASA's Artemis mission, shown in Figure 12, and the capabilities needed for a HLS on Mars would be similar to a one for the Moon, albeit with higher thrust to overcome the higher gravity of Mars.

Docking

The HLS Modules and Starships will dock with the RUBBER I in the 'front' module. (The module before the nosecone) (See Modules) This has two main advantages over docking in other modules:

- More space, especially when compared with the middle module (which is connected to the centrifuge and the solar panels)

- Less consequences in the event of a failure, especially when compared with the back module (which stores fuel tanks)

Footnotes

Is Nuclear Really Safe?

We, at Astro Forge Technologies, sincerely believe that using Nuclear Power on our ship is safe. There will be shielding on the RUBBER I, to protect crew members from potential radiations from the MMRTG and the nuclear engines. Furthermore, there are a small amount of accidents from nuclear power, especially over the last few years.